By Paul Horton.

This is the fourth in a series. Here are the prior posts:

Part 1: Historians and the “Lost Cause” of the Confederacy

Part 2: The Confederate “Lost Cause” and Southern Women

Part 3: Confederate Monuments and Southern Memory: The Case of One Confederate General

When Alabama state Rep. William Dismukes proudly shared on social media that he had attended a birthday celebration for the first grand wizard of the KKK, Nathan Bedford Forrest, at the same time that the passing of John Lewis was being commemorated with a solemn last walk across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, many across Alabama, the South, and the country were outraged.

Similarly, when Arkansas senator Tom Cotton declared that slavery was a “necessary evil,” many reacted in shock.

Many of the supporters of southern politicians like Dismukes and Cotton are quick to label the angry responses to what they said as “political correctness” or the “cancel culture” that characterizes what they think is the strident moral absolutism of the Black Lives Matter agenda.

But the reactions of those who are disgusted with the utterances of Dismukes and Cotton also fail to make important historical connections beyond the simple fact that Forrest was the founding leader of the Klan.

Dismukes and Cotton grew up learning a very narrow construction of Southern “heritage” that is based on one narrative: the narrative of history as Southern white nationalism as preserved in the “Lost Cause” created by the Dunning School and organizations like the United Daughters of the Confederacy.

They grew up reading versions of their state histories that systematically ignored the stories of slaves, freedmen, and Southern Unionists.

To be sure, there is some awareness today of the raising of the United States “Colored Troops” (USCT) in the South that stems in part from the popularity of the 1989 film, “Glory” and its depiction of the heroics of the 54th Mass. USCT. And African American descendants of USCT have recently mustered into “reenactment” regiments. But most Southern school children learn little about the bravery of those who fought in over 100 regiments who escaped slavery in the deep South to fight for their freedom, and who knew that they would receive, to use Tom Cotton’s phrase, “no quarter.”

Likewise, many doubtless know about localities that seceded from the Confederacy because local citizens did not want to fight to keep slavery in a “rich man’s war.” Some have heard about the “free state” of Jones in Mississippi and the “free state” of Winston in Alabama where an historical drama reenacts the vote not to secede led by C.C. Sheets who was elected to congress during Reconstruction. But few Southerners learn of the true extent of Unionist disaffection and persecution of Unionists during the war by Confederate Conscription Cavalry, although they might have seen or read about this persecution in the movie or the book, “Cold Mountain.”

Huge areas of the South resisted secession and resisted cooperation with the Confederate army and were brutally pacified, but never completely subdued. These areas include eastern Tennessee, western North Carolina, portions of eastern North Carolina, western Virginia, northwestern Tennessee, northern and eastern Alabama, northern Georgia, northeastern and southwestern Mississippi, northern Louisiana, northwest Arkansas, parts of the Red River Valley of Texas, and the Hill Country of Texas, where most settlers were liberal 48ers who escaped Germany after a failed revolution in many cities in what eventually become Germany.

I have written a micro history of one county in northern Alabama that attempted to weave together the narratives of the Confederate nationalists, Unionists, and the enslaved who became freedmen. (“Submitting to the ‘Shadow of Slavery’: The Secession Crisis and Civil War in Alabama’s Lawrence County,” Civil War History, 1998; )

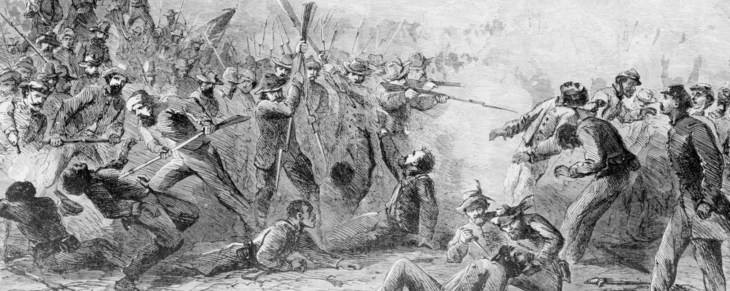

The history that few Southerners know is the history that links all three of these narratives. Because Dismukes and Cotton really only know one narrative well, they do not understand that General Forrest and his command were responsible for the slaughter of hundreds of USCT troops from Alabama at Fort Pillow Tennessee after they surrendered, giving brave men from Alabama “no quarter.” These Alabama troops escaped slavery by following the command of Union general Grenville M. Dodge (famous for building the transcontinental railroad after the war) after Dodge had raided the Tennessee Valley of Alabama. Hundreds of these freedmen resided in the Corinth Contraband Camp (northeastern Mississippi) under the protection of the United States army and were mustered into the USCT there. They were stationed, trained, and drilled in what is today south Memphis, a former Union fort. From Memphis, they were deployed to Fort Pillow where they met their fate at the hands of Forrest’s troopers.

My point here is that the Dismukes and Cottons of our world cannot make the connection that to celebrate Nathan Bedford Forrest is to celebrate a man who was responsible for murdering African American troops.

Dismukes and Cotton also do not understand that some of the sociopathic troopers of Forrest and his fellow cavalry commander in the Confederate Army of the Tennessee, Joseph Wheeler, were active soldiers in the KKK during and after Reconstruction. Many of these same troopers who committed murders of disarmed Union soldiers and war refugees at Fort Pillow, Tennessee and Ebenezer Creek, Georgia also committed murders of freedmen and Republican political activists as Klansmen in Alabama, Tennessee, Georgia, Mississippi and Arkansas.

One such trooper who fought with Wheeler and was present at Ebenezer Creek where hundreds of unarmed Black civilians were killed assassinated Wheeler’s chief postbellum political rival to clear the way for Wheeler’s long career as a US congressman in the 1880s and 1890s. (“The Assassination of James Madison Pickens and the Persistence of Anti-Bourbon Activism in North Alabama,” 2004:

Only by studying many narratives, and piecing together multiple stories where they overlap, will we be able to reassemble Southern history in such a way as to honor the lives of all Southerners. Racial healing in the South requires a confrontation, discussion, and reconciliation of multiple narratives.

Those who support Dismukes and Cotton need to open their hearts and learn a more complex Southern history.

Paul Horton is History Instructor University High School, The University of Chicago Laboratory School

Leave a Reply