By Paul Horton.

Part 3: Confederate Monuments and Southern Memory: The Case of One Confederate General

Part 4: Where “Southern Heritage” Falls Short

Part 1:

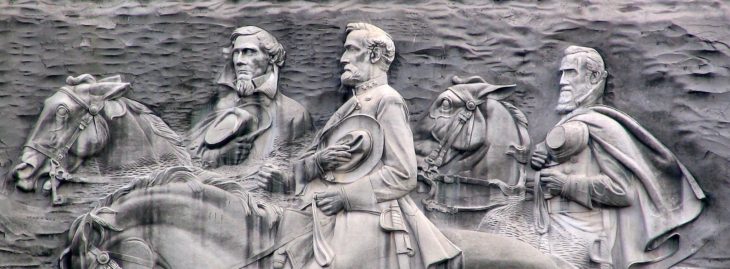

In town squares and public parks across the nation, monuments and memorials commemorating the heroes of the Confederacy are being questioned and even pulled down. Most Confederate monuments and memorials were constructed between 1890 and 1920. It is important to understand the context surrounding the construction of Southern monuments for many reasons.

First, 1890 represents the rise of what historian Joel Williamson calls, “racial radicalism.” Beginning with the rise of the biracial Knights of Labor, the formation of the Union Labor Party, and the biracial Agricultural Wheel, concerted efforts were made to unite white and black farmers and unions made a concerted effort to reach out to African Americans following the successful “great southwestern railroad strike” of 1884. When a second railroad strike failed in 1886 and the Haymarket “Riot” resulted in the dissolution of the Knights of Labor, the Union Labor Party sought to resurrect an inclusive biracial farmer-labor party in 1888. It was during the 1888 election season that marked the beginning of “racial radicalism” that was characterized, according to Williamson, by a rapid rise of racial threats, intimidation, and lynchings that would increase virtually every year until 1920. When black and white farmers and laborers came together to form the Populist Party in the early 1890s, the Klan in the South was reconstituted in paramilitary form to suppress biracial political cooperation. When Southern states successfully rewrote constitutions to disfranchise blacks and many poor whites, the threat to white supremacy represented by biracial farmer-labor parties in the South was replaced by the one-party Jim Crow South.

Second, as the frontier closed and the debate about imperialism was engaged in the 1890s, northern and southern politicians deemed it necessary to join together in the creation of a nationalist culture necessary to construct an extra-territorial empire. For “reunion” to take place, the nation had to bind the wounds it suffered during the Civil War and southerners and northerners had to agree to stop waving the “bloody shirt.” Reunions that brought soldiers from both sides together were held at important battlefields, John Phillip Souza’s martial music replaced “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” and “Dixie” on town bandstands, and Southerners put the past to rest by constructing monuments to fallen heroes while northern public officials and Supreme Court justices ceded civil rights to states. When political leaders decided to fight Spain in Cuba, the Confederate “boy general,” Joseph Wheeler, was placed in a command position, symbolically reconstituting the United States military.

Third, as the country was reunited symbolically in the 1890s and early twentieth century, a new school of southern history won the Civil War in academia. The so-called Dunning School based at Columbia University rewrote Southern history to describe the Reconstruction period as a catastrophe for the South. William A. Dunning and his graduate students wrote a series of histories of southern states during reconstruction that essentially downplayed the intelligence and agency of freedmen and southern unionists and sympathized with and underestimated the violence perpetrated by groups such as the Ku Klux Klan and the Knights of the White Camellia.

At the time that most southern monuments were being constructed, popular histories written by members of the Dunning School were read and discussed by members of groups that shaped southern memory. These perspectives are also reflected in Thomas Dixon Jr.’s novel, The Clansman, and in the subsequent film, “The Birth of a Nation” that premiered in early 1915 and was shown, despite protests from the NAACP, at Woodrow Wilson’s White House. Sociologist and historian W.E.B. DuBois would author the first full scale scholarly critique of the Dunning School in 1935 in his Black Reconstruction which raised serious questions and supplied convincing evidence to challenge the Dunning School’s paradigm of Reconstruction history. In the 1950s, historians Kenneth Stamp and C. Vann Woodward extended DuBois’s critique of the Dunning school and, in 1988, Eric Foner, using primary sources never before used in his, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolutionfinally blew up the Dunning School’s perspective by placing the agency of freedmen at the center of the dissolution of slavery during the Civil War and at the fulcrum of the push for civil rights during Reconstruction.

As the above discussion suggests, “Lost Cause” history that was created to recapture the heroism of leaders of the Confederacy who fought to preserve slavery as many white southerners, novelists and historians included, were seeking to whitewash the complexities of that same history. Slaves, freedmen, and southern unionists were left out of the dominate narrative of Southern History.

Because southern “Lost Cause” history, southern identity, and neo-confederate nationalism based on white supremacy have been so persistent in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, many historians have sought to explain why. Below is a sampling of these analyses.

1) As you read the following excerpts think about how the descriptions are similar and different.

2) What is the “Lost Cause”?

3) Is the “Lost Cause” an important part of Southern identity now? Explain.

4) Is the “Lost Cause” by definition a racist concept?

Gaines M. Foster, Ghosts of the Confederacy: Defeat, the Lost Cause, and the Emergence of the New South (New York and Oxford, 1987)

Southerners’ response to the first attempt to mobilize them in memory of the Confederacy demonstrated their resolve to accept defeat and their hesitancy to go off on romantic crusades. In the 1870s a coalition of organizations headquartered in Virginia began what amounted to a Confederate revitalization movement. Jubal A. Early and the other leaders of its constituent groups fit the stereotype of proponents of the Lost Cause. They brooked over defeat, railed against the North, and offered the image of the Confederacy as an antidote to postwar change. While not tied closely to the planter class, the leaders of this movement came from the prewar southern elite and from among the leaders of the Confederacy. They wrote much history that influenced the South’s interpretation of the war, but they never created a successful movement. Their organizations attracted few members, and they failed to build an institutional base outside Virginia. Their vision of Confederate revitalization interested few southerners.

Extreme enthusiasm for and extensive participation in Confederate activities developed much later, toward the end of the 1880s. For the next twenty years or so, southerners celebrated the Confederacy as never before or since. Veterans all over the South joined not the Virginia organizations but a new group, the United Confederate Veterans. Nearly a hundred thousand southerners each year journeyed to one city for the UCV’s reunion and a general festival of the South. The Sons and Daughters of the Confederacy also formed at this time. And most of the stone Confederate soldiers on town square sand courthouse laws were put up during the same years. Although the Confederate celebration had its roots in persisting anxieties resulting from defeat, increasing fears generated by the social changes in the late nineteenth century provided the immediate impetus for the revived interest in the Lost Cause. In the public commendation of the Confederate cause and its soldiers, veterans and other southerners found relief from the lingering fear that defeat had somehow dishonored them. At the same time, the rituals and rhetoric of the celebration offered a memory of personal sacrifice and a model of social order that met the needs of a society experiencing rapid change and disorder

The Lost Cause, therefore, should not be seen, as it so often has been as a purely backward-looking or romantic movement. The Confederate celebration did not foster a revival of rapid sectionalism. With the exception of a few disgruntled and unreconstructed die-hards, its leaders and participants preached and practiced sectional reconciliation. Although in no way admitting error, their accounts of the war emphasized not the issues behind the conflict but the experience of battle that both North and South had shared. The Lost Cause did not signal the South’s retreat from the future, but, whether intentionally or not, it eased the region’s passage through a particularly difficult period of social change. Many of the values it championed helped people to adjust to a new order, to that extent, it supported the emergence of the New South.

pp., 5-6

1) What were the origins of the Lost Cause according to Foster?

2) What groups pushed for the preservation of southern Civil War memory initially?

3) When did widespread enthusiasm for the Lost Cause develop and why?

4) What role did honor play in the development of Lost Cause thinking?

5) How can the Lost Cause be distinguished from backward-looking nostalgia?

Charles Reagan Wilson, Baptized in Blood: The Religion of the Lost Cause, 1865-1920 (Athens and London, 1980)

White supremacy was a key tenet of the Southern Way of Life, and Southern ministers used the Lost Cause religion to reinforce it. The implications of the Lost Cause for racial relations were disturbing. The Ku Klux Klan epitomized the use of the confederate experience for destructive purposes. The Klan represented the mystical wing of the Lost Cause, as the most passionate organization associated with this highly ritualized civil religion. Its mysticism was attained not through a disciplined mediation, but through the cultivation of a mysterious ambience, which fused Confederate and Christian symbols and created unique rituals. The racial views expressed within the context of other Lost Cause institutions were more moderate than the Klan’s. Race itself did not play a large role in the Confederate myth, where the central focus was on the virtue of the Confederates. Southerners insisted that they had fought for principle, not for slaver, and the Negro’s wartime loyalty was a respected part of the Lost Cause myth. The special concern of Lost Cause ministers was the obstacle that postbellum blacks presented to the preservation of a virtuous Southern civilization. The ministers’ views on this subject thus reflected the essential concern of the jeremiad; one could see here, as elsewhere, that the Lost Cause vision of the good society was paternalistic, moralistic, well ordered, and hierarchical.

The post-Civil War years saw segregation emerging to replace slavery as the South’s solution to the “race problem.” Southerners were united in believing in white supremacy, but historians have identified several different positions within the general acceptance of white dominance. After the instability of Reconstruction, the position that dominated the 1880s was the paternalist-conservative one, closely aligned with the New South business philosophy. The paternalists typically rejoiced at the demise of slavery, but they nostalgically praised the harmonious race relations of the antebellum period. They saw no place moral or cultural decline after the Civil War, and they stressed that the races had continued their harmonious relations. The second position, which came to dominate after 1890 and especially after 1900, was of negrophobia. The Southern position partly reflected the nationwide growth of Anglo-Saxon racism in this era. The extreme racists of the South believed that the Negro was a beast, and that he had sunk to a morally degenerate condition when the discipline of slavery had been removed. They advocated right repression and control, which meant trick public segregation at the least, and which some even extended to the justification of lynching.1

Southern ministers were among the leading defenders of white supremacy. As H. Shelton Smith has suggested, racial heresy was more dangerous to a preacher’s reputation than was theological speculation. White Southerners perceived dissention on the racial issue as a threat to the social order itself, and clergymen made clear their commitment. One could find ministers whose views fell into each of the two major racial positions, although few religious leaders succumbed to extreme racism. Most typically the clerics preached acceptance of Negro inferiority and white supremacy, while working to mitigate the harshness of the system through individual cases of charity and kindness. The attitude of ministers of the Lost Cause did not precisely fit either of the two dominant categories; they were paternalists, but their attitudes came from a different source than those of the New South paternalists. Lost Cause belief focused on the moral retrogression of blacks after emancipation, but preachers articulated this idea before extreme racism of the end of the century made it a dominant article of faith. The belief in moral retrogression stemmed from the legacy of slavery, the blacks’ behavior in the Civil War, and the Reconstruction experience.2 The fear of Negro decline was the basis for both racial positions associated with the Lost Cause—the extreme Ku Klux Klan viewpoint, and the most moderate paternalistic-moralistic position. The Klan represented negrophobia, while the Lost Cause paternalists tried to find a substitute for slavery as a way of insuring Negro virtue and thus Southern virtue.

- 100-101

1) In what ways was the Lost Cause connected to religion?

2) How were religion and racism connected in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century American South?

David W. Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American History (Cambridge and London, 2001)

Three overall visions of Civil War memory collided and combined over time: one, the reconciliationist vision, which took root in the process of dealing with the dead from so many battlefields, prisons, and hospitals and developed in many ways earlier than the history of Reconstruction has allowed us to believe; two, the white supremacist visions, which took many forms early, including terror and violence, locked arms with reconciliationists of many kinds, and by the turn of the century delivered the country a segregated memory of its Civil War on Southern terms; and three, the emancipationist vision, embodied in African Americans’ complex remembrance of their own freedom, in the politics of radical Reconstruction and in conceptions of the war as the reinvention of the republic and the liberation of blacks to citizenship and Constitutional equality. In the end, this is a story of how the forces of reconciliation overwhelmed the emancipationist vision in the national culture, how the inexorable drive for reunion both used and trumped race. But the story does not merely dead-end in the bleakness of the age of segregation; so much of the emancipationist vision persisted in American culture during the early twentieth century, upheld by blacks and a fledgling neo-abolitionist tradition, that it never died a permanent death on the landscape of Civil War memory. That persistence made the revival of the emancipationist memory of the war and the transformation of American society possible in the last third of the twentieth century.

- 2-3

1)According to Blight, what were the three narratives of memory about the Civil War?

During the 1890s, three entities took control of the Lost Cause: the United Confederate Veterans (UCV), founded in 1889; a new magazine, the Confederate Veteran, founded in 1892 and edited in Nashville by Summer A. Cunningham; and the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC), founded in 1894. Both the UCV and the UDC grew rapidly as organizations that complemented one another. The UCV was born in New Orleans in June 1889, out of a growing impulse among local veteran organizations to amalgamate into larger groups. Survivors’ associations and associations of particular armies had long engaged in fraternal support and local remembrance. But as the national reunion took hold, so did ex-confederates seek more national forms of expression. The UCV’s first commander-in-chief was former U.S. Senator and then governor of Georgia, John B. Gordon. Gordon was a New South politician with heroic credentials, and he provided an eloquent voice for both Confederate memory and reconciliation on Southern economic and political terms. By 1896, the UCV had 850 local camps, and by 1904, they had 1,565. The geographical distribution of UCV camps included at least one in 75 percent of the counties of the eleven former Confederate states. The best estimate of membership in the UCV seems to be 80,000 to 85,000 in 1903, a peak year.32 Appealing to the interests of the ordinary veteran, especially against the fears and trials of the 1890’s economic collapse and political turmoil, the UVC became a safe haven of comradeship and celebration for the full range of Lost Cause attitudes and rituals.

For its part, the UDC spread across the South and also established some chapters in the North. By 1900, the UDC boasted 412 chapters and 17,000 members in twenty states and territories. By World War 1 it may have had as many as 100,000 members engaged in a wide variety of memorial activities. The generally well-heeled UDC women were strikingly successful at raising money to build Confederate monuments, lobbying legislatures and Congress for the reburial of Confederate dead, and working to shape the content of history textbooks. They distributed tens of thousands of dollars in college scholarships to granddaughters and grandsons of Confederate veterans. The UDC ran essay contests to raise historical consciousness among white Southern youth, and by the turn of the century they had launched an ongoing campaign to designate “War between the States” as the official name for the conflict. In all their efforts, the UDC planted a white supremacist vision of the Lost Cause deeper into the nation’s historical imagination than perhaps any other association. Working largely from women’s sphere as guardians of piety, education, and culture, many UDC members nonetheless led public-activist lives; although most opposed women’s suffrage, many of their leaders were intensely political people. Behind, and often at the center of, every Confederate reunion (their pictures adorning the pages of nearly every issue of the Confederate Veteran) were UDC women, old and young, the “auxiliaries.,” “sponsors,” and “maids of honor” without which the Lost Cause could not have dominated Southern public culture as it did.

- 272-273

1)How did the Lost Cause become the dominate narrative of Southern memory?

- Fitzhugh Brundage, ed., Where These Memories Grow: History, Memory, and Southern Identity (Chapel Hill and London, 2000)

The construction of historical monuments in the nineteenth-century South (and elsewhere in the United States) illustrates these fictions. Public monuments were portrayed by purportedly voluntary associations (which, in fact, often had close ties to officialdom) as spontaneous expressions of popular enthusiasm and reverence. Such groups invariable summoned the public to contribute funds and provide support for commemorative projects. Eventually, after months, even years, of fund-raising, sculptors were hired, designs approved, and then completed monuments unveiled before the gathered public. The monuments that emerged from this process frequently were testimonials to popular enthusiasm, but neither was the enthusiasm spontaneous nor the “public” necessarily one people united by shared memory. Yet once the monuments were erected, the origins and struggles of the sponsorship and design of public monuments receded into the background (until some latter-day controversy exposed them). Whatever the particular motivations of the promoters of the memorials, their monuments to Confederate soldiers, loyal slaves, Revolutionary-era patriots, and local dignitaries became sacrosanct and in time defined the enduring image of the “public” that purportedly erected them.36 Only by piercing the appearance of immutable collective memory can the struggles over the power to define, include, excise, and interpret the past be seen.

- 13

1)How do monuments become collective memory, according to Brundage?

White women assumed the leadership in erecting monuments, preserving historic sites, creating historical displays. Likewise, women’s organizations supplied classroom materials, conducted classes to “Americanize” immigrants, funded college scholarships, and crusaded for the teaching of “true history” of the South, especially with regard to slavery and sectional strife. White women of the New South, in sum, asserted a cultural authority over virtually all representations of the region’s past.38

The essential point is that many white middle-class and elite women found in history an instrument for self-definition and empowerment. Within the boundaries imposed by the prevailing beliefs of the era, the meaning of the collective memory of the white South was open to multiple readings which in turn allowed white women to use it for varied purposes. The historical activities of white women legitimated contradictory claims for power, some reactionary, others emancipatory. For many white women, their gendered identities could not be separated from their ties to the past—not just their personal, familial past, but also the collective “History” of the South. Beset by the transformations of the New South, elite white women found in history a resource with which to fashion new selves without sundering links to the old. The study of historical memory, then, forms an important element of any understanding of the construction of social identities.39

p.14

1)What was the perspective of the middle class white women who constructed confederate monuments?

How can we explain the conspicuous popularity of Confederate symbols in a region that was noted for widespread Unionist sentiment during the Civil War and that subsequently resisted the memorialization of the Confederacy during the apogee of the “Lost Cause” movement? Answers to these and similar questions will clarify the symbiotic relationships that often exist between the remembered past of dominant groups and the counter-memories of the marginalized.

p.23

1)How did the construction of Confederate monuments bury the history of Southern Unionists?

Kirk Savage, Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-Century America (Princeton, 1997)

… the destruction of slavery bore fruit not in genuine liberation of the black body but in transformation of the white hero and the white body. It was the very failure to create a real interracial order in sculpture that enabled the rise of new forms of public sculpture commemorating Anglo-American heroism. A whole new type of public monument emerged dedicated for the first time not to the illustrious hero but to the ordinary white man, the generic citizen-soldier who had fought in the war on both sides (see figs. 6.1-6.2, see below). This redefined what commemoration was all about and what war memorials were meant to be. In 1866 Howells had proposed that the memorials of the war should be about emancipation; within a few years it was taken for granted that they were inscribed not on the bodies of African Americans but on the body of Abraham Lincoln, so the moral imperatives of citizenship came to be inscribed on the bodies of white soldiers—profoundly reshaping the image of the soldier and the nation in the process.

- 18-19

1)According to Savage, why were monuments after the Civil War almost exclusively of white soldiers?

To write this history, we must recognize, along with other recent scholars, that whiteness is itself a racial category. Whiteness, in Cornel West’s words, is “parasitic” on blackness: the ruling category is unnecessary, even meaningless, without its negative counterpart.34 Decades ago, Winthrop Jordan in his landmark study White Over Blackdemonstrated how English colonists did not arrive in the New World as “white”; they gradually adopted this term to separate themselves from the “blackness” they had imported in the form of African slaves. More recently, David Roediger and Noel Ignatiev have examined the process by which nineteenth-century Irish immigrants overcame their identification with oppressed blacks and learned instead to be “white.”35 My study confirms that in the public sphere the creation and recreation of whiteness is inseparable from the creation and recreation of blackness. The marginalization of African America went hand in hand with the reconstruction of white America. African Americans could not be included or excluded in the landscape of public sculpture without changing the fabric of commemoration itself, without ultimately changing the face of the nation.

The story of the marginalized cannot therefore be understood without rewriting the history of what became dominant. This is why the current literature that seeks to document exclusion—from public art, public sculpture—does not go far enough.36 The recognition of the racist power relations that drive such exclusions is a necessary first step. But that recognition does not amount to an analysis of the racial formation of dominant culture. If the subject of race teaches us anything, it must teach us to revise the history of what is included in the dominant culture.

- 19-20

1)How is the creation of “whiteness” inseparable from the creation of “whiteness” in American history?

Confederate soldier monuments in the South have sometimes met with protests. Richmond’s Monument Avenue, that public bastion of white supremacy, was finally “integrated” in the summer of 1996 with a monument to Africa American tennis player Arthur Ashe, designed by sculptor Paul D. Pasquale. The statue was added despite significant opposition and only after wrenching debate over the meaning of Confederate commemoration in today’s South.1

The Ashe Monument offers a lesson in the continuing power of public monuments. On my many visits to monument Avenue before the Ashe statue was contemplated, I never saw a soul—white or black—actually look at the Confederate heroes enshrined there. One might easily have thought that over time the monuments had lost all significance. But that appearance was deceiving. Even after the collapse of segregation and the demise of white rule in Richmond, the Confederate monuments remained powerful because they functioned within the civic landscape as a last bastion of white privilege. Their importance was demonstrated most palpably when African American leaders, in the early 1990s, began to try to alter Monument Avenue’s image by proposing monuments to black heroes—originally heroes of the Civil Rights movement. Many local whites dug in to “protect” the Confederate landscape from such a direct assault on its guiding principle.

- 211-212

1)According to Savage, why are Confederate monuments by definition racist? Do you agree or disagree with his analysis? Why? Why not?

Using your responses to the above questions and the texts above write a two to three-page essay in response to the following statement:

“Confederate monuments are legitimate ways to honor the memory of fallen war heroes” Agree or disagree with this statement.

You may use internal documentation to cite the sources above.

Paul Horton is History Instructor University High School, The University of Chicago Laboratory School

Featured Image by Peter Kaminsky. Used with Creative Commons license.

Leave a Reply