By John Thompson.

The 50th anniversary of Jonathan Kozol’s Death at an Early Age comes as we confront the horror of the Charleston, S.C. massacre and the epidemic of police killings of unarmed blacks. At a time like this, it is best to read Kozol’s masterpiece on its own, without using it as evidence for any side of our current edu-political conflicts. After a decent interval for letting the tragedies sink in, we can then draw upon it as we debate contemporary school policy.

The subtitle of Death at an Early Age is The Destruction of the Hearts and Minds of Negro Children in the Boston Public Schools. It is an unrelenting indictment of the segregated Boston Public School System in 1965. Back then, I was twelve years old and I didn’t know a single black person, and George Washington Carver was the only black person in our textbooks. It was easy for an Oklahoman like me, however, to grasp the overt racism of “the Redneck.” As Kozol knew, it would be far harder to comprehend the covert racism of “the Reading Teacher.” As he guides us through his quest to understand the Reading Teacher, however, Kozol reveals the disgusting soul of Boston’s curriculum, its governance, and its segregation.

The Redneck seemed to be the most honest teacher in this predominantly poor and black elementary school. He’d been treated rough while growing up and so were the black children who he was supposed to teach. The Redneck exemplified the mentality of “we did it, and we never had any fancy schools either.” He said he was just as “culturally deprived” as Negroes, and:

I don’t need anyone to tell me. I haven’t learned a thing, read a thing that I wished I’d read or learned since the day I entered high school, and I’ve known it for years and I tried to hide it from myself and now I wish I could do something about it but I’m afraid it’s just too late.

In perhaps the most straightforward conclusion in Kozol’s nuanced analysis of prejudice and segregation, he observed, “Former Irish boys beaten by Yankee schoolmasters may frequently make ungenerous teachers for little boys whose skins were black.”

Wrapping our minds around the Reading Teacher is a much more formidable and painful task. She was a liberal and a supporter of civil rights. Although the Reading Teacher was completely vested in their horrible school’s mission, she also was capable of sometimes seeing its failures. Teachers complied with the school system’s mandates out of fear but even the Reading Teacher was capable, in an “excited whisper,” of confiding, “Can you imagine how this principal honestly and truly can stand there and call herself an educator?”

The Reading Teacher’s educational values were very consistent with Boston’s “A Curriculum Guide in Character Education.” It sought to instill in students values such as obedience, perseverance, and gratitude. Implicit in this goal was the need for Negro students to unlearn the value systems of their homes and communities. In fact, when Kozol was ultimately fired for “curriculum deviation,” he was charged not with reading a black poet to his class but for reading a poem, Langston Hughes’s “The Landlord,” that doesn’t “accentuate the positive.” He was fired for reading a poem that “does not present correct grammatical expression and would just entrench the speech patterns we want to break.”

Perhaps the best way to understand the system’s approach to proper curriculum as a path to proper conduct is to contemplate the lesson Kozol learned when he used a phonics book, Wide Doors Open. The children were yawning as Kozol read. But, after the lesson, the kids pretended they enjoyed it. They described the lesson as “Interesting,” “humorous,” “colorful,” and “adventurous.”

Those were all words on the “permissible list,” which was displayed behind Kozol. The students “had simply assumed that, because I had asked the question, one of those words must be the right answer.”

Subsequent questioning revealed that the students saw the lesson as “babyish” and “boring.” Kozol realized that “the terrible thought that there was a right answer and that I already knew it and that it remained only for them to guess was the most disheartening thing of all.”

When Kozol tried to discuss this insight with the Reading Teacher, her final retort was, “At least it shows that they know the words on the list.”

The Reading Teacher’s approach would have been to “sell” the book “to call it wonderful and to sweep them over with a wave of persuasive enthusiasm.” She thought she was equipping Negro children to survive in their harsh world. In fact, she “had equipped them with a set of tools to keep themselves at as far as possible a distance from the truth.”

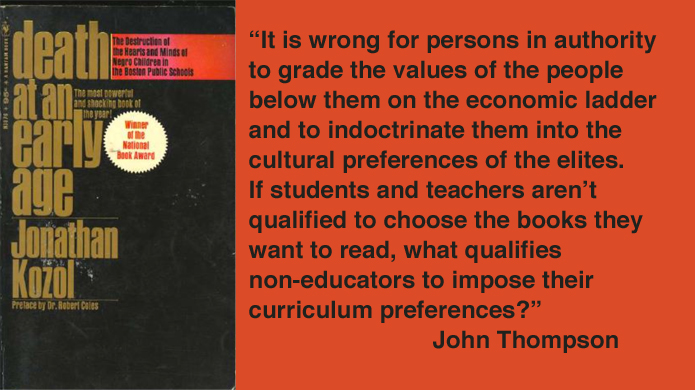

For me, the lessons of Death at an Early Age are obvious. Until schools produce a society of lifelong learners, we will continue to produce persons like the Redneck. Until we have economic justice, teachers and other employees will live their working lives in fear. Top-down governance systems will always prove and reprove the maxim, “Power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” It is wrong for persons in authority to grade the values of the people below them on the economic ladder and to indoctrinate them into the cultural preferences of the elites. If students and teachers aren’t qualified to choose the books they want to read, what qualifies non-educators to impose their curriculum preferences? And, the quest for the “right” answers is false and degrading.

But, I’ve intentionally kept my interpretations brief and at the end of a summary of the book’s passages that I believe are self-explanatory. As was shown by the heroic and loving congregation in Charleston, however, we need open dialogue. I hope that all participants in education’s reform war will read Death at an Early Age.

What do you think? Could we get a wave of book club discussions of Kozol’s book? If so, what would be the result?

Kimberly Kunst Domangue

You would be pleased by the New Business Items passed at this year’s NEA RA, Mr. Cody. Social justice was the order of the day, every day. State caucuses debated their positions, then brought the debate to the floor of the entire assembly! It was very much in keeping with Mr Kozol’s work; however, we refrained from using terms such as “redneck”. Toxic testing was the other primary issue.

This was an interesting read. A book club would be an interesting activity to share with other education professionals a Ross the country. Note: The school term in LA resumes mid-August, and our friends in Chicago have not been able to engage in well-deserved rest due to contract shenanigans of smarmy-reformy-Rahmies.

Anyhoo, good read, all the same.

Gayle

I have read Death at an Early Age many times over the years. Still a powerful classic (and I don’t think you touched on the most powerful parts). I’d love to discuss it. Got a copy right on my bookshelf.