By Anthony Cody.

In California, legislators will soon have a chance to approve AB 101, a new law that would task the state superintendent with developing a plan to promote the creation of elective courses in ethnic studies across the state.

Ethnic studies is clearly important for students of color, who find themselves marginalized in society, and in our curriculum as well. Students need to see themselves and their ancestors represented in the history they learn. This is a basic human right – not to be made invisible, but instead to be seen and have their stories told. Ethnic studies is also of great potential benefit to all of society, in that learning about systemic racism allows us to confront it directly. Research has shown that ethnic studies and diversity courses benefit students of color and whites as well.

Jose Lara, vice president of the El Rancho Board of Education, explained this:

Studies show that Ethnic Studies empowers students to preform academically and think critically. It is an educational justice demand teachers and students have been making since the modern civil rights movement. It is our duty as board members to listen to the people and follow the research that says Ethnic Studies improves academic achievement and a more equitable society.

Some of the research that Lara is referencing was done in Tucson, Arizona, where a strong program in Mexican American Studies (MAS) was dismantled a few years ago by Republican state leaders (as I wrote about in 2010). Four University of Arizona professors investigated the program to determine its impact, and what they found was remarkable. Their report, available here, discovered that the program had a strong positive effect on students:

The MAS students had significantly lower 9th- and 10th-grade GPAs as well as 10th-grade AIMS scores than their non-MAS peers. However, they had significantly higher AIMS passing and graduation rates than their non-MAS peers, which seems counterintuitive. Decades of findings from education research would lead us to expect higher 9th- and 10th-grade GPAs and higher 10th-grade standardized test scores to be positively correlated with higher graduation rates (Alexander, Entwisle, & Horsey, 1997; Rumberger, 2011). Instead, we found the MAS students outperformed their non-MAS peers in terms of AIMS passing and graduation despite having 9th- and 10th-grade academic performances that were significantly lower (see Table 2). These results corroborate findings that ethnic studies can lead to increased student development (see, e.g., Astin, 1993; Bowman, 2009, 2010a, 2010b; Sleeter 2011).

In 2011, the National Education Association published this report by Christine Sleeter which examined research on the effects of ethnic studies programs. Sleeter found that the curriculum presented in our schools remains largely Eurocentric. Students of color become aware of this as early as middle school and this contributes to a sense of alienation. But ethnic studies courses can help combat this.

Sleeter reports that:

In sum, all but one study investigating the impact of ethnic studies curricula designed for members of the group under study found a positive impact on students. Three studies documented high levels of student engagement when literature by authors of the students’ ethnic background was used. Research on five literacy curricula documented significant growth in students’ literacy skills. Research on two math/science curricula found a positive impact on student achievement and attitudes toward learning. Research on five additional curricula, mainly in social studies, found a positive impact on students’ achievement and sense of agency. It is important to stress that these curriculum projects, on the whole, were well-designed, and taught by teachers who were prepared in ethnic studies and who, for the most part, were themselves members of students’ ethnic group.

It is easy to understand why students of color who feel marginalized and invisible in the mainstream curriculum would gain a sense of identity and confidence when given courses that honor their ancestors and critically examine the power structures they are encountering as they approach adulthood. This is a compelling reason to advocate for these courses.

Last fall, I spoke with college student Hannah Nguyen about ethnic studies, and she said this:

A curriculum that includes ethnic studies exposes students to the stories and ideas of different cultures and backgrounds fosters a learning environment that is both diverse and accepting. This is a curriculum that will not only create good students but also good people with open minds and hearts. An ethnic studies curriculum teaches its students to see the one another’s humanity, to feel empathy for one another’s struggles, and to cultivate a passion for social justice. But most importantly, it adds significance to the education of children of color, who will no longer feel invisible and ignored but rather engaged and empowered in their own learning as they learn their own histories and use that understanding to connect to the larger community.

Sleeter’s research also showed where white students and teachers would benefit from ethnic studies.

White adults generally do not recognize the extent to which traditional mainstream curricula marginalize perspectives of communities of color and teach students of color to distrust or not take school knowledge seriously. Epstein (2009) found that, while White teachers were willing to include knowledge about diverse groups, they did so intermittently and within a Eurocentric narrative. She found that White parents, like their children, “thought only of Europeans and white Americans as nation builders, portrayed Blacks as victims and one-time freedom fighters, and Native Americans as first survivors and later as victims of government policies. They never mentioned Whites (other than Southerners) as perpetrators or beneficiaries of racism and 80 percent believed that Blacks had achieved equal rights today.”

This means white teachers are not well equipped to combat the alienation we see in children of color. Our schools are often not responding in a proactive way, but instead join in the mainstream narrative that we are on some conveyer belt of history moving inexorably towards a color-blind society. This does not prepare white teachers or students to engage in the work that continues to be needed to combat systemic racism.

Sleeter’s research also found that when white students took their first course taking on issues of diversity they experienced emotional challenges, but this can be overcome.

In a large survey study of students in 19 colleges and universities, Bowman (2010a) examined the impact of taking one or more diversity courses on students’ well-being and on their comfort with and appreciation of differences. He found that many students who take a single diversity course experienced a reduced sense of well-being due to having to grapple with issues they have not been exposed to before. However, students who took more than one diversity course experienced significant gains, with gains being greatest for White male students from economically privileged backgrounds (who had the farthest to go). Completing a diversity course also appears to mitigate what is otherwise an escalation of intolerance in the university experience.

As a white male growing up in California in the 1970s and 80s, I found ethnic studies courses to be highly beneficial. I learned the value of ethnic studies firsthand when, as a high school student, I learned US history through the lens of Chicano History. At community college a few years later, I studied African American history with Professor Henry Bryant, and Asian-American History from Gordon Chang. And at UC Berkeley, I learned more about Chicano history from Alex Saragoza. Each of these classes challenged traditional myths of how the United States came to be, and helped me understand the unpaid debts owed to people who were robbed, kidnapped, or subjected to genocide in the building of our nation. These patterns extend into our economic and social system today, as has been revealed by conflicts such as the killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson. Today’s racial flashpoints can only be understood when we examine the history that led us here. On an individual basis, white people can begin to understand how systemic racism continues to carry benefits for whites, and costs for people of color, when we learn this history. Then we can better work as allies to people of color in dismantling these systems.

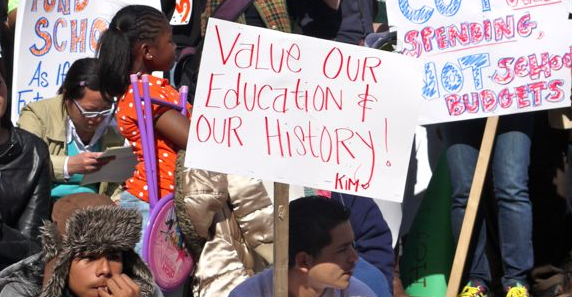

Activists in a group called Ethnic Studies Now have been pushing to expand such classes in the state for several years. I wrote here last November about efforts in Los Angeles and San Francisco to create such programs. The bill is supported by the California Teachers Association, the California Federation of Teachers, and United Teachers of Los Angeles. I asked UTLA’s vice president, Cecily Myart-Cruz, why the unions are supporting the bill, and she said,

We support this because we believe it is a fundamental right for students to have access to diverse curricula. Students begin to feel empowered when they have courses connect them to their own cultures and to the cultures of others as well.

If you live in California, please contact your state legislator to let them know that you support AB 101.

What do you think? Is it time for an expansion of ethnic studies courses in our schools?

Dana R.

It is important that those living in America FIRST learn American history and the uniqueness of the American system. It is also important that ethnic studies do not paint America as the evil enemy like the Re Conquista movement does. If those two things are thoroughly addressed FIRST. then I see that it could be a good thing, but I want to know when the real history and suffering of the Irish will be included or does my ancestors’ experiences not matter because they are white?

Cheryl

@ Dana R…

Wow, your Irish ancestor’s were kidnaped from Ireland to be inslaved in early America?