by Paul Horton. Part one of three.

My son and I took our annual road trip last week. We listen to books on tape and blues as we travel. He is learning to drive so, for the first time, he was able to take the wheel for hours at a time while I bit my fingernails and chewed my gum.

On the morning of our arrival to the Delta that most Chicago south and west siders call home, he put on his Levi’s jeans jacket and told me to stop on the shoulder before with reached the intersection of US highways 49 and 61.

I dutifully pulled over and waited, he had handed me his camera, but he was taking a long time. When I turned around to see what he was doing, I saw that he was adjusting his sunglasses, his jacket, and taking his Stratocaster out of its case and handling it like a newborn baby. He then smiled and walked slowly to the intersection road signs. It occurred to me at his point that that he had rehearsed these moments in his dreams and that this was, the crossroads where Robert Johnson made a pact with the devil at midnight. We stopped at 10 am and I don’t think I saw any unexplained shadows, but my son was making an evil smile for the camera, and we will see how his playing has improved in the next few weeks.

We visited several blues museums and cultural centers because my son and I know, as Einstein was fond of saying, that the separation of the past, the present, and the future is a willfully ignorant illusion. Every true southerner, black or white, man or woman, and everybody in between knows this and it makes us all as crazy as Faulkner’s Quentin Compson looking at his reflection in the Charles on a Cambridge bridge, The past is not past.

When I saw the riding crop encased in glass, a shiver went up my spine and the goose bumps followed the icy cold shadow that had passed through me, not dissimilar to the visceral presence of evil that enshrouded my spirit as I neared the ovens at Dachau—the presence of bone chilling absolute evil. I knew what that horsewhip had been used for. I knew it in my bones.

Bill Branch, the curator of the exhibit that displayed the riding crop at the excellent Delta Cultural Center in Helena, Arkansas, told me that he displayed the horsewhip instead of a bull whip because too many visitors could not bear the sight of a bullwhip. The horse crop was made in 1850 and it symbolized the absolute, almost feudal power of the planter class in surrounding Phillips County the Delta region, a region that fanned out south, west, and northwest of Memphis, the economic hub of the mid south, an area described by historian Nan Woodruff as “The American Congo” to suggest a level of brutality that surpassed the violence that the Belgians inflicted on their rubber colony.

Branch said that he wanted visitors to understand that the blues came from heat, from nonstop cotton chapping and picking, and from the ever-present reality of the whip. The blues, Branch’s exhibit suggested represented the only legitimate public form of free speech available to most of the residents of the Delta.

Having spent much of my adult life studying the history of this area, I knew that Mr. Branch knew what he was talking about. I have read through the county histories of the region that were published in the late nineteenth century and remember that Phillips County contained twenty Klan “dens” from 1868 to the mid 1890s, according to local historians. A high level of Klan organization was typical of counties with a two to one black to white ratio in the Delta region.

The Ku Klux Klan was organized in early 1868 by ex-confederate soldiers who resurrected their Civil War command structures within a new political party that called itself “the party of the white man,” otherwise known as the Democratic Party.

The Klan used the whip and the pistol to deny free speech, voting rights, and the civil rights protections for all promised in the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the Fourteenth Amendment to African Americans and whites.

Integrated schools were attacked, burned, black and white teachers were warned, whipped, and murdered for daring to articulate and insist upon the enforcement of equal protection and due process rights for all.

After the Klan and the Democratic party “redeemed” white supremacist white rule in the south in the wake of Reconstruction, they refused to allow a voice for those who insisted on civil rights, due process, fair elections equal education funding, and an end to convict labor to have a voice within the party.

When the planters who dominated the “party of the White man” refused a place for Democrats who sought to protect due process rights and fund education equitably, Democrats with a small “d” joined white and African American Republicans in the Greenback–Labor Party, a party that might be more accurately called the teacher-preacher party.

Successful in many local areas, these coalitions often carved out local governments, school boards, juries, tax assessors, law enforcement that respected due process and equal protection rights.

The Agricultural Wheel, an organization of farmer cooperatives, and later the Populist party, also insisted on protecting black and white “small fry” despite attempts of white supremacist power brokers to suppress these organizations. The Agricultural Wheel in Phillips County, Arkansas, was exceptionally powerful, creating an interracial local government that sought to protect cotton picker’s due process rights. In a nearby county, the Wheel led to a massive cotton strike. In Leflore County, Mississippi, across the river, however, an attempt made by black pickers to start independently operated and supplied stores for the county’s farmers led to a massive military assault by the Klan, organized by local planters who had a monopoly on stores and credit lines, and the region’s “big mules,” the board and members of the Memphis Cotton Exchange that supplied and controlled credit lines for the entire Delta region. Black farmers who resisted the Cotton Exchange’s idea of “free enterprise” were targeted for erasure. As is often the case with many such events in the deep south, according to Historian William F Holmes, we will never know how many local African Americans were murdered trying to defend the equal protection of their rights within the “free enterprise system.”

The whip and the pistol were used to deny equal protection and due process.

The gritty dirt farmers and teachers and preachers simply would not give up, though. Even after voting rights had been denied to most blacks and poor whites in most states, a massive uprising by cotton pickers brought about brutal repression after WWI in what can only be described as a war against the poor, and when the New Deal denied farm subsidies to the “small fry” in the Delta, black and white farmers in the Arkansas Delta formed the Southern Tenant Farmers Union (STFU) that spread like wildfire throughout the South. If you ever read a memoir of one of these tenant farmers, Nate Shaw (All God’s Dangers) you will be amazed by the courage of these farmers who demanded self respect and the right to organize and bargain collectively. They were hunted like animals by local and regional law enforcement, held without charge indefinitely, and murdered and lynched without trial, without any due process. The denial of due process, equal protection, and habeas corpus, and the collective bargaining protections extended to unions in the north, not to mention lynchings and murders of STFU members prompted outcries from within liberal New Deal circles, but FDR famously looked the other way because he needed the votes of key southern senators to continue to pass bills. The Democratic Party stood at the crossroads when it came to due process for the poor in the South, a story told in painful detail in historian Ira Katznelson’s, Fear Itself.

The accommodation of southern racism hung like an invisible shadow over the Democratic party until another fearless movement forced the hands of Kennedy and Johnson, who correctly predicted that the Democrats would lose the South for a generation for its support of several major laws in the sixties that restored equal protection and due process rights. These were the rights that so many brave southerners had sought and sacrificed their safety and well being, and in many cases their lives for over 100 years, if we include the contributions of southern freedmen and unionists in support of a union victory in the Civil War.

As a philosophy, accommodation has been a key factor in both the Republican Party’s “southern strategy” that worked to peel off southern white Democrats and in the recent attempts by Clinton and Obama to win back “Reagan Democrats.”

Both parties have pandered to the prejudices of southern white voters on issues as diverse as law and order, gun control, and affirmative action and desegregation.

Coming next: Part Two: The Obama Administration’s War on Teachers

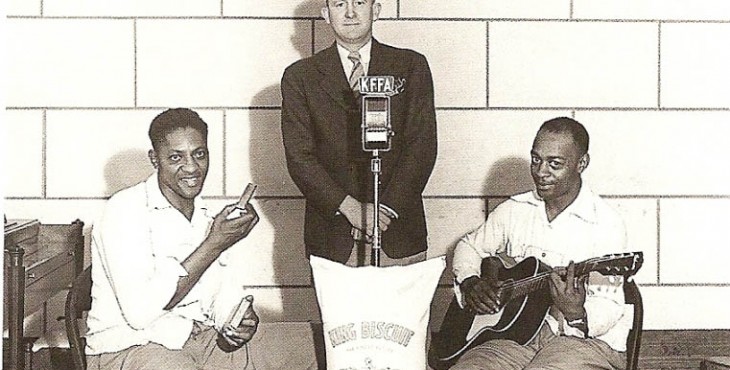

Featured image: Sonny Boy Williamson II (Rice Miller), KFFA Owner Sam Anderson, Robert “Junior” Lockwood in King Biscuit Time Promotional Shot in Helena, Arkansas – 1940s (Photo Courtesy of Terry Buckalew of KFFA)

john a

Re part 1. Your journey was a great gift to you and your son.. With the past and present holding hands, you son leans that the past does not evaporate, as do the years What impressed me was that you made conscious a piece of Southern history that has become lost: there was a time when poor whites and black were in alliance of the economic conditions that oppressed them. There is a viable radical piece of southern history which takes into account the progressive elements of Populism. I tends to be buried or otherwise ‘forgotten’. Despite its limitations you should read (if you haven’t already) “The Populist Response to Industrial America”, by Norman Pollack.

Paul Horton, Citizens Against Corporate Collusion in Education

Pollack is very good! A classic! American biracial populism is a legacy that should be remembered. I forgot to link to the Elaine Massacre in Phillips County, Arkansas in 1919. Just google “Elaine Massacre.”

john a

I read Pollack way back in 1967, while a student at NYU. On a different note, damn, I would have thrived at a school school such as the Lab School. Unfortunately I went to a public high school with 4000 students, triple sessions, 35 kids in a class. I ‘zombied through four years. Alas. Your students should realize that they have been presented with the gift of a super fine, albeit elite education; the type of education that should be available to all. But you know that already.

Deborah Duncan Owens

We can learn much by exploring the history and legacy of racism in the U.S. As a former teacher in Mississippi and professor of education in Arkansas, I learned a great deal about the reality of how this legacy has impacted our country and, in particular, education policy. While teaching elementary school in MIssissippi I had the privilege of working with the William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation at the University of Mississippi. We were successful in passing Senate Bill 2718 which ensured that civil rights history would be taught as part of the K-12 curriculum in Mississippi (http://winterinstitute.org/wp-content/blogs.dir/1/files/2013/08/WellspringJan07.pdf).

We should not forget the horrific events associated with slavery and racism. However, we should also come to terms with the impact this legacy has had on public school policy. In fact, conservative free market ideas were first lauded in southern states seeking to find ways to maintain segregated public schools. Now these ideas have become mainstream. I examine these issues in my book The Origins of the Common Core: How the Free Market Became Public Education Policy (to be released in January, 2015 by Palgrave Macmillan), devoting an entire chapter to Milton Friedman and Friedmanomics policies that have come to dominate discussions about education policy in the U.S. For Friedman, school choice/vouchers/charter schools were the panacea for any and all school policy issues. His ideas have been embraced by every presidential administration since Reagan. Segregation was not a problem for Friedman. As a matter of fact, federal intervention to desegregate schools was the problem for Friedman. In addition, in chapter 2 I explain how southern segregationists opposed to school desegregation played their part in a conservative coalescence that helped in the election of Ronald Reagan.

Paul Horton, Citizens Against Corporate Collusion in Education

I will be sure to read your book. I have written a few pieces on these issues too. The Chicago Graduate School of Business is right across the street from my school.