By Chris Thinnes.

(A Review of Stuart Grauer’s Fearless Teaching, forthcoming Jan. 2016 from AERO)

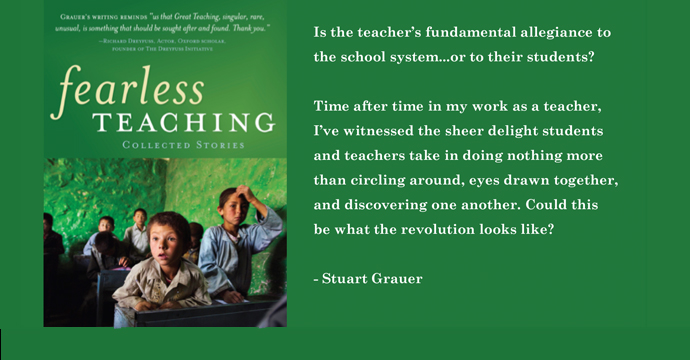

Is the teacher’s fundamental allegiance to

the school system…or to their students?

Time after time in my work as a teacher,

I’ve witnessed the sheer delight students

and teachers take in doing nothing more

than circling around, eyes drawn together,

and discovering one another. Could this

be what the revolution looks like?

– Stuart Grauer

“The progressive educator,” Paulo Freire told us, “must always be moving out on his or her own, continually reinventing me and reinventing what it means to be democratic in his or her own specific cultural and historical context” (1997, cited in Darder, 2002, p. 5). Stuart Grauer, founder of The Grauer School and The Small Schools Coalition, honors this call to action in Fearless Teaching (2016, forthcoming from AERO), and leverages his experiences and insights from an admittedly privileged positionality to offer a unique lens on cultures of teaching and learning to which some of us may not have access, and in which some of us may fear to tread — partnering with Californian students on partnership excursions to small schools in Cuba, Korea, Navajo territory, Palestine, Panama, Tanzania, and many other places around the world.

At first Grauer’s strategy is disarming and discomforting, as it moves well past the conventional frames of debate in contemporary discourse on education reform and education policy — past the Thunderclap campaigns and Twitter wars; past the white papers, conference panels, and political platforms — to meditate on some simple truths best revealed through the unfamiliarity of the experiences and discoveries in the wide swath of local cultures he represents. It took me some time to figure out what, exactly, Grauer was “up to” — daring not to allude all too often or too thoroughly to contemporary American education debate — until I stumbled upon his reference to Rumi: “Beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing / there is a field. I’ll meet you there” (p. 47). Indeed, Grauer meets us there, and asks us in Fearless Teaching to look beyond the “narration sickness” from which education suffers (Freire, 2000, p. 71), to look into each others’ eyes, to speak honestly, and to listen deeply.

What he finds may come — initially, at first — as no solace to those of us who fight to maintain any semblance of radical hope for a more systemically humanizing pedagogy in the contemporary American educational landscape:

Everywhere I travelled, in all corners of the world, whether affluent or disadvantaged, I was finding teachers largely focused on their ever-increasing workload and ever-decreasing time as they attempted in good faith to comply with a rigid lineup of state and national requirements. We are making ourselves exhausted. (p. 175)

The result of this global tendency, of course, is a generation of students on a global scale who are increasingly alienated from their experience of learning in schools. Asking new colleagues in South Korea “what their problems were in helping students be happier” (p. 192), Grauer concedes that the answer came as no surprise:

I hear this answer from progressive teachers, conservative teachers, teachers who are fresh and starting out, and teachers who are fed up. Their answer was the same as that from pretty much every single teacher in every forum in which I have taken part in the last several years. And that answer was, in the developed world, teachers feel penalized for curriculum they are supposed to cover in a year but can’t get to in time. Add to this, they feel demoralized that their worth and fate as professionals are determined by the standardized test scores their students get at the end of each year they spend in this race. (p. 193)

In “Teaching as an Act of Love,” Antonia Darder confirms that, in these times, “teachers, besieged by the politics of expediency and the standardization of knowledge, feel little freedom to practice the flexibility to permit the learning process to emerge organically with students” (Darder, 2002, pp. 123-124). Elsewhere examining the threads of a Freirean “pedagogy of love,” Darder acknowledges that–

In many ways, what Freire understood is what so many educators accidentally discover–when students genuinely experience the freedom to think and their imaginations find an open field to express themselves, they often work far harder and with greater discipline, enthusiasm, and joy than they do when they are forced into antidialogical modes of teaching that sentence them to prescriptive regurgitation of fixed knowledge–knowledge that is abstracted and decontextualized from their lived histories and their active presence. (2015, p. 99)

Fearless Teaching is a unique, consuming, and transformative mediation on a pedagogy of listening that, despite the ostensibly forcing constraints of prevailing education policy and popular teaching practice, will be necessary to make visible a Freirean pedagogy of love. By no accident Stuart Grauer begins with his most eloquent articulation of the core principles of this pedagogy, as he wonders whether educators might well be served by making a “Socratic Oath” to their callings, analogous to the Hippocratic Oath doctors make to theirs: “First listen. Observe. Prevent no learning” (p. 3). Through such principles, Grauer argues, “we can discover a new definition of teaching: the study of the student” (p. 37). For we must acknowledge–

The research says what we already know, that people are not only happiest, but most productive when they are with people they care about. A great teacher understands that engagement is not primarily about the subjects studied or the required curriculum and testing — it is about the relationships that are forming in the class. Connection . . . is the single most important thing in all of pedagogy. (p. 215)

With such a commitment to listening — a deeper listening; a more purposeful ‘hearing’ — we might together reinvigorate a pedagogy (and the “untested feasibility” of a policy) that acknowledges and honors the fullness of the humanity that both student and teacher bring to their essential and reciprocal relationship. This requires an immense vulnerability on our parts as educators:

Sufi teachers refer to this as “the wisdom of the idiots.” Over time, if we are lucky, we may learn how little we know, and this is the essence of Socratic teaching. We stop disguising our vulnerability and weakness, we sense that our view of the world is oblique and naive, and so we pursue our teaching and service as a way to access our own larger awareness and connection. The great teachers, it seems, are those willing to take off their armor and drop the role-play, at least from time to time. This is the field where we at last meet our own selves in the most natural way in the world, so that we can meet our students. (p. 38)

This resonates with and responds to Freire’s indication that “Education must begin with the solution of the teacher-student contradiction, by reconciling the poles of the contradiction so that both are simultaneously teachers and students” (2000, p. 72). This resonates as well with a more transformative vision of “education transformation” itself than tends to be proffered by prolific pundits and wonks. Through Grauer’s lens we can see the “untested feasability” (Freire, 2000, p. 102) made visible, of a future of schooling more like Carla Rinaldi has framed it:

We will find the new and the future in those places where new forms of human coexistence, participation, and co-participation are tried out, along with the hybridization of codes and emotions… The new thus seems to lie in promoting an educational process based on the values of human dignity, participation, and freedom. (Project Zero & Reggio Children, 2001, pp. 45-46)

Recently Curtis Acosta shared with Progressive Education Network conference attendees the words of Luis Valdez, inspired by Mayan epistemology and pedagogy:

|

|

Sit down with Stuart Grauer’s Fearless Teaching, but set aside a few hours on a Saturday to digest it in a single sitting worthy of the “one-day respite from educational incarceration” (p. 6) it offers. Do not expect a thoroughgoing critique of American education policy, an adequate assessment of ethnic or racial inequities in the American educational, social, or political landscapes, or a purposeful deconstruction of privilege, scarcity, or other complex dynamics underlying the dynamics of public and private schooling in the United States. Do expect a contemplative, insightful, provocative, and potentially transformative meditation on a “pedagogy of listening” that might bring solace, could help us to ideate solutions, and will reinvigorate our shared commitment to relational learning that honors the shared humanity of teachers and students alike.

As Grauer himself concedes:

When you are out there, doing a separate thing, following your heart, sometimes you wonder how crazy you might be, and at those times it’s reassuring to check in with someone you trust…So you can keep doing it. (p. 214)

Trust Stuart Grauer. Do a separate thing. Follow your heart. These may be “small things,” Grauer concedes–

But, perhaps, they unchain the joy of doing, and translate into actions. Because after all, taking action in the real world and changing it, despite the little that change may be, is the only way to prove that reality is transformable. (p. 257)

Chris Thinnes is a learner, leader, and consultant in Los Angeles.

References

Darder, A. (2002). Reinventing Paulo Freire: A pedagogy of love. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Darder, A. (2015). Freire and education. New York, NY: Routledge.

Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of the oppressed (30th anniversary ed). New York: Continuum.

Grauer, S. (2016). Fearless teaching: Collected stories. Roslyn Heights, NY: Alternative Education Resource Organization.

Project Zero & Reggio Children. (2001). Making learning visible: Children as individual and group learners. Cambridge, MA & Reggio Emilia, Italy: Reggio Children Publications.

Leave a Reply