By Anthony Cody.

In the wake of the unindicted killing of Michael Brown, the roots and ramifications of racism in America have been brought to the surface once again. One of the constructive ways that educators can respond to this challenge is through Ethnic Studies courses.

On November 19, the Los Angeles Unified School District school board voted to make Ethnic Studies a required course for every high school student. This action has inspired a similar move in San Francisco, where the school board will vote on an ethnic studies proposal on December 9. Backers of the initiative are asking supporters to wear red and show up to a rally prior to the board meeting. They are also asking people to sign and share a petition, here. This video shares student voices in support of the proposal.

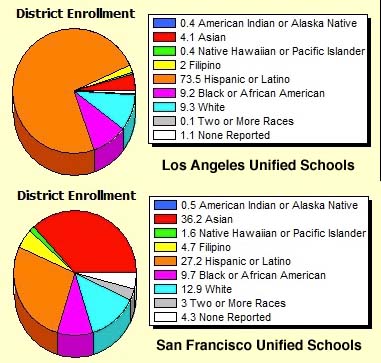

Public schools in Los Angeles are attended by students from all over the world – more than 90 languages are spoken. The table below shows the ethnic breakdown. About 90% of the students there are of color, and almost three fourths are Latino. San Francisco likewise has a majority of students of color, with large Asian and Latino populations.

The current wave of enthusiasm for ethnic studies in California has its roots in recent history. In Tucson, Arizona, a successful Mexican American Studies (MAS) program became a political target for state lawmakers, who passed HB 2281, which outlawed programs that “promote resentment of any race or class,” “advocates ethnic solidarity instead of being individuals,” or are “designed for a certain ethnicity.” The law was challenged in court, but was upheld.

Research into the impact of the Mexican American Studies program showed it had a very positive effect on the students who enrolled. Here are a few of the indicators from this 2012 report:

There was a significant, positive relationship between MAS participation and passing the AIMS [Arizona Instrument to Measure Standards] Reading test for two of the four cohorts (2008 and 2011). Students in the 2009 cohort just missed the significance cut off as the p-value was 0.052. For the 2011 cohort, MAS students were 101 percent more likely to pass their AIMS Reading test, and 2008 MAS students were 168 percent more likely to pass than were non-MAS students.

Finally, there was a positive relationship between MAS participation and passing the AIMS Math test. In the 2008 and 2009 cohorts, MAS students were 144 percent and 96 percent more likely to pass the AIMS Math than non-MAS students.

Students who took MAS courses were between 51 percent more likely to graduate from high school than non-MAS students (2009) and 108 percent more likely to graduate (2008).

There are clear reasons why ethnic studies has a positive impact on students. One of the sponsors of the Los Angeles resolution, George McKenna, explained: “There is a saying: ‘The real story of the hunter will be told when the lion and the buffalo get to write,’” The director of the MAS program in Tucson, Sean Arce, explained this:

Racism is about control and marginalization and dehumanization of a group of people. In no means are we being that. Our pedagogy, our curriculum, is about rehumanization, about race as a social construct. And it’s about not replicating this paradigm. The real question we have to ask is, what type of power do certain groups of people wield against certain groups of people?

In San Francisco, supporters of Ethnic Studies say this:

Through the examination of counterstories and often times neglected narratives of all people, students learn to humanize and respect themselves, their families, and their communities. Students will think critically about race, ethnicity, and culture in the context of their own identities and their lived experiences

Kyle Beckham is a former San Francisco teacher, who taught Ethnic studies in continuation school for the past decade. He is active in the Ethnic Studies Teachers Collective, a group of educators pushing for expansion of the program. I asked him why he was so supportive.

What I noticed was that Ethnic Studies (ES) pedagogy and content had transformative potential. I say both because ES done well is a mindset that a teacher has as well as particular content. Teachers who understood that the content needed to be delivered in a way that was tied to a way of seeing students, of treating students, had the greatest success. So it was not merely the presentation of facts or even alternative histories, but the manner in which these things happened. The students most moved by ES were those who were most willing to be critical, to be political and to struggle towards developing themselves.

The content was the hook, it was the thing that made them pay attention, but that only goes so far. Most of the ES pedagogy in SFUSD is rooted in activity and doing something. Of building a real praxis. Students write an autoethnography focused on race, nationality, ethnicity and language. They interview family members (and are taught ethnographic techniques for doing this well). They do Youth Participatory Action Research around issues that are important to them (integrating local, national and international struggles in the process).

Many kids that the collective of teachers in SFUSD taught would say that ES changed their lives, that it made them see the world differently and that they felt like they had tools to change things. As much as opponents think of it as indoctrination, it is pretty far from it. Students were to question any and everything. To question the official story, to question the alternative and to decide for themselves. But the key was that they were to question and be critical (media literacy is a key component of the curriculum to name one specific example).

I think that many people have this idea that ES is what it was in the 60s, and there has been a mountain of intellectual work and scholarship done since then that has made it something much bigger than what was going on back then. What did/do I want as an educator? I want students who will engage with the world, who will fight and struggle to make it better and who are critical of themselves and what is presented to them as “truth.” Ethnic studies allowed that to happen and it continues to happen in the classrooms of the teachers committed to it.

I have some personal experience with Ethnic Studies. At my own high school, in the 1970s, I took Chicano History to fulfill my US History requirement. At Laney College, I studied African American history. And at UC Berkeley, I took Chicano History again. I was never taught to hate my own ethnic identity, though I became aware of the many ways in which events of the past continue to influence our lives today. These courses helped me to understand the complex issues I encountered as a teacher in Oakland.

Student activist Hannah Nguyen, who recently graduated from high school in San Jose, California, and now attends USC, offered this perspective:

A curriculum that includes ethnic studies exposes students to the stories and ideas of different cultures and backgrounds fosters a learning environment that is both diverse and accepting. This is a curriculum that will not only create good students but also good people with open minds and hearts. An ethnic studies curriculum teaches its students to see the one another’s humanity, to feel empathy for one another’s struggles, and to cultivate a passion for social justice. But most importantly, it adds significance to the education of children of color, who will no longer feel invisible and ignored but rather engaged and empowered in their own learning as they learn their own histories and use that understanding to connect to the larger community.

There is a petition here to support the expansion of Ethnic Studies in San Francisco. The San Francisco Board of Education will vote on Tuesday, December 9, 2014. There will be a rally prior to the meeting — both will take place at 555 Franklin Street, San Francisco. The rally will be at 5 pm and the meeting at 6 pm. Supporters are asked to bring signs and wear red.

Update, Dec. 12, 2014: The San Francisco school board this week voted to approve Ethnic Studies for all students starting next fall. Details here.

Featured image by the True Colors Mural Project.

carolinesf

Expand ethnic studies, absolutely. Don’t REQUIRE it. Kids need flexibility, not more rigid requirements.